Ideally, we want every element of the propeller blade to be flying as efficiently as possible. This is available online at the NASA Technical Reports Server. One of the best references on this subject is NACA Technical Report 640, published in 1938. NACA did many tests on propellers to determine the effects of diameter, solidity, and number of blades on propeller performance. At this point, increasing the solidity and total blade area of the propeller by increasing the number of blades is a better design option than increasing the chord of a smaller number of blades.Īs we see on some modern turboprops, when the power gets large, a high-solidity prop with many blades is often the best solution. The blades get heavy, and the structural issues of joining a large blade chord to a practical shank and hub get severe. If the blade chord gets too large, several problems appear. Up to a point, increasing blade chord works well. As power increases, it becomes necessary to increase blade area and propeller solidity to absorb the power in the diameter allowed. Since most light airplane engines turn at about the same speed, we can see that the maximum propeller diameter hits a practical limit very quickly. As we have seen, the diameter of the propeller is often limited by other factors to a lower-than-optimal size. In practice, this is only true if the designer has the option of choosing the theoretically ideal propeller diameter to absorb the power of the engine. Theoretically, increasing solidity decreases efficiency because the blade parasite losses increase with increasing blade area. A high-solidity propeller has a large blade area relative to its disk area. The solidity of a propeller is the ratio of the blade area to the area of the disk swept by the propeller. If they are too small, they may stall before the pitch reaches a high enough value to absorb the power of the engine. If the blades have too much area, the parasite drag of the blades will hurt efficiency. Increasing either blade area or blade pitch increases the amount of power the propeller will absorb, so proper design involves finding the proper balance between area and pitch. The blades must have enough area and pitch to absorb the power delivered by the engine at the right rpm. The parameters available to achieve this are blade area, blade airfoil, blade planform, number of blades, and pitch. Once the diameter of the propeller is set, the designer must come up with a blade design that will absorb the power of the engine at the proper rpm and convert it to thrust as efficiently as possible. Tip Mach number becomes less of a limit because the prop rpm can be chosen to keep it at an acceptable value, and ground clearance and propeller weight start to become more important limiting factors.įor extremely large propellers, blade structural considerations, both strength and stiffness, can limit the maximum feasible diameter as well. If the engine is geared, the designer can adjust propeller rpm, as well as diameter, to get to an optimum design point. On a direct-drive engine, the full-power rpm is set by the engine characteristics, and this in turn limits the diameter of the propeller.

Diameter Limitsįor most airplanes the propeller diameter is set primarily by a combination of tip Mach number and landing gear length considerations.

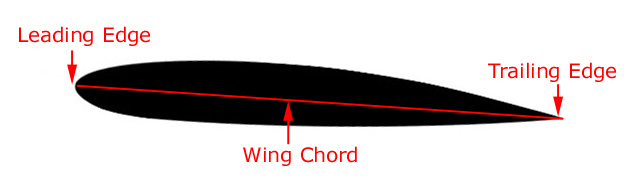

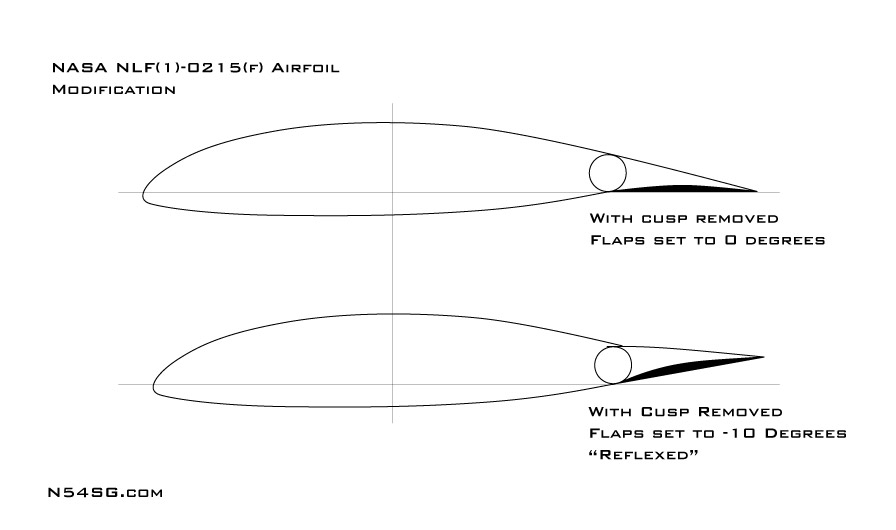

Accordingly, the airfoil and planform choices for a good propeller are different than those for a good wing. As we have seen in previous months, the airflow conditions along the length of the blade vary in a much different way than on a wing. Like a wing, a propeller blade is characterized by its area, planform, and airfoil cross section. We now turn our attention to some more details of the shape of the blades themselves.

In our discussion of propellers so far, we have covered basic momentum theory and taken a look at the characteristics of the incident airflow on the blades.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)